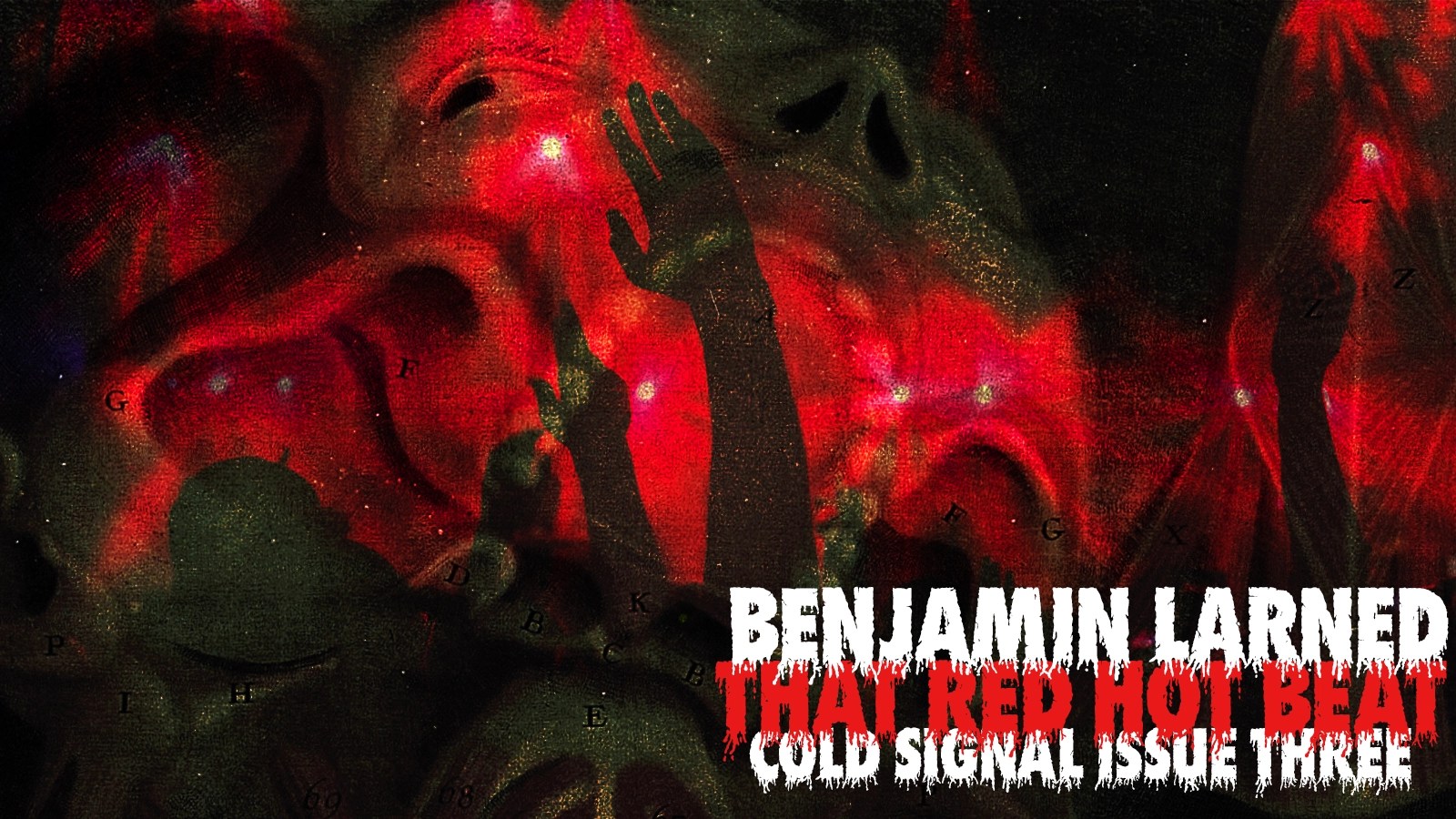

That Red Hot Beat

by Benjamin Larned

“Do you ever get a song stuck in your head? A song that doesn’t exist?”

Jerry Logan snorted the question through his nose. Across the table of the overpriced restaurant, Caroline said without inflection, “Never.”

“I do,” Jerry said. “I have to, like, purge them or I lose my shit.”

Looking up from her phone, Jemima noted, “That’s a sign of genius.”

“I get them too,” slurred Joe, pink-faced from mezcal. “I wake up humming stuff I’ve never heard of.”

“Maybe you have a bad memory,” Jerry laughed, and signaled across the restaurant. “Where the fuck is my check!”

Caroline was trying very hard not to despise Jerry. He made his living as an influencer, uploading several violent prank videos a week, each of which gained millions of views. Her brother considered him a close friend, ever since they’d bonded at a drug-fueled warehouse party. “This could be huge for me,” Joe had shouted when he’d called Caroline that morning, still high.

Jerry and his entourage had left Los Angeles for image rehab due to a scandal involving racial slurs. Joe had offered to host in Denver where his sister Caroline still lived. She’d show them a good time, he promised.Caroline, a night-shift nurse, had no interest in showing anyone a good time. She wanted nothing more than to sleep and forget about people like Jerry, but Joe was her baby brother, and she intended to look after him.

After splitting the check four ways, the group trailed into the barren January night. Jerry sighed a plume of steam. “What are we doing?”

Joe sprung to attention. “Union Station is cool, lots of craft cocktails. Or we could go brewery-hopping –”

Jerry rolled his eyes and yawned. Jemima pulled out her phone, muttering as she typed, “This place is sad. How do people live here?”

Caroline watched Joe’s shoulders droop, his eyes zoning into the ground. He might have curled into a heap before them, had a voice not spoken, “There’s always the Mouth.”

The voice belonged to a thin man in a fedora and long gray trench coat. The cold didn’t seem to touch him. Caroline felt in her pocket for cash, but the man was not begging, just standing awfully close.

Casting a wary glance at him, Joe asked, “What’s the Mouth? Is it new?”

“Not so new.” The man’s lips twitched into a wormy smile. “It’s well-hidden. Exclusive.”

“Where is it?” Jerry demanded.

“Past the old dog food plant, just off the highway as you go Northwest. They’ll turn all that into apartments soon, but until then…”

Caroline knew about the plant – she drove past it every day with a shiver of melancholy – but she’d never heard of these parties. She had assumed that Denver was too small for an underground scene.

The man turned towards Caroline. “I should warn you, it’s not for everyone. If you’re not meant to be there, they’ll know.”

“How do we get in?” Joe asked, but the man had vanished, folded into the winter night.

“Let’s go to the Mouth, then,” Jemima said, with a laugh at the name. “Maybe it’s cute.”

As they waited for a rideshare, Caroline thought of the man’s last words. They’ll know. She wasn’t keen to find out who they were. This city harbored a unique brand of weirdos; any number of strange groups might be hiding on the outskirts.

“Maybe we should go somewhere closer,” she said to Joe. “It’s pretty late.”

“If your sister is too tired, Joseph, maybe you should take her home,” Jerry said. “I’m not in the mood to babysit.”

“I’m older than all of you.”

Jerry didn’t look at her. She might have grabbed the fucker by his shirt, told him what she really thought had their car not pulled up that moment. “Come on, grandma,” Joe mouthed. Caroline sneered at him from the passenger seat.

As the car rolled past churches and convenience stores, Caroline readied herself for the impending ordeal. She had never liked parties, all of which seemed to end with her clutching the toilet, pining over a straight girl or wondering where things had gone wrong.

Her life as a nurse suited her more. Her aunt, grandmother, and a few cousins were all nurses, humble and overworked, but steadfast and resourceful as well. She knew that Joe thought she had settled. His ambitions were big and urgent, but she never understood what exactly he aspired to. She wasn’t sure that he did, either, if he chose to align with people like Jerry Logan.

The car reached the suburbs, where strip malls gave way to houses and condos, flat cutouts in the dark. The dog food plant loomed on the horizon, then blew past. The driver took the next exit, into the flatirons.

“I didn’t know they built anything out here,” Caroline said – a stupid comment; they had built something everywhere.

The driver said, “Just some houses. Never finished them. I drop people off here sometimes, but I don’t pick them up. Parties must go all night.”

The hills rose around them, parting to reveal a cul-de-sac. There were no street lamps along the row of houses; the headlights alone revealed their giant facades.

The driver stopped by one of the larger models, done like a theme-park villa. Jerry and Jemima slid out, shouting at the cold. “We’re in the middle of nowhere,” Jemima whined.

Caroline thanked the driver. He replied, “Good luck,” and skidded away.

They stood under the wide black sky a while, gazing up at the houses around them. As Caroline tried to see through the windows, she wondered who might peer back. The doorways could be full of watchers with no lights to give them away.

“Look!”

Joe pointed toward a house around the bend, thrumming with artificial blue and purple and bright, burning reds. Hints of bass came from the sagging roof, which had fallen in at the center.

Caroline’s eardrums preemptively ached. The house didn’t look safe, hardly capable of withstanding a crowd. But Joe and his friends were already crossing the driveway. With a last glance at the silent hills, Caroline dragged behind.

The bouncer stopped them at the porch, a tall, leathern woman in a tattered red gown, fingers coated in silk, broad shoulders impervious to cold. “Do you have any idea who I am?” Jerry asked her.

“Doesn’t matter who you are.” Her voice was deep, unbothered. “You’re not going to find what you’re looking for here.”

“If we don’t like it, we can just leave,” Joe challenged.

The bouncer scrutinized him with iron apathy. “Are you sure about that?” She raised an eyebrow at Caroline.

Joe grumbled, “Of course I’m sure.”

The bouncer smirked – a wormy twitch, like the trenchcoat man’s – and stepped aside. “Alright then. If you’re ready.”

The door opened onto a heaving mass of bodies. The crowd melted into each other beneath a mist of sweat and spit, wearing shredded coats, dresses, pants ripped to the crotch. They draped and dangled from every surface, even the chandelier, which looked unable to support their weight. Caroline could make out faces on the upper floor, chanting at the swingers to “bring it down.”

And through them all, through the air, the walls, her extremities and core, vibrated an inescapable beat.

Jerry bobbed out of the front room into a den lit by deep purple. The group followed, first Jemima, then Caroline and Joe. The ceiling stretched high above them, too dark to see. Even so, Caroline felt claustrophobic. If a fire broke out, this place would be a death trap.

She turned to Joe but someone had replaced him, a wan girl whose pupils reflected the room like a wet mirror. Jerry and Jemima had vanished as well. The beat changed and the mist hung lower in the air. Sleek faces seemed to populate the room exponentially in an amoebic soup.

Caroline pushed against the bodily current. They jostled her back into the front room, under the chandelier. The ceiling had cracked at its anchor.

She forced herself away from it and ran into Joe, who looked equally glassy-eyed and lost. Wondering how much time had passed, she shouted, “What’s wrong?”

He muttered something; she screamed back, “What?”

He repeated like a heartbroken child, “I can’t find them.”

“Good riddance, they’re fucking assholes.”

“What did you call them?”

“Your friends suck. They treated me like shit all night. You too. They’re only here to get away from bad press, right?”

Her brother’s face wilted. “It’s not their job to make you feel good. They work hard, they have a lot of demands on them. Sometimes they –”

“Sometimes they what? Forget how to be a person?” She tried to stop, but the beat drove the words from her throat. “They’re not gonna help you. They’ll forget about you like they’ve probably forgotten about me.”

“You’re just jealous that he’s famous, and you’re going to be a wage slave for the rest of your life.”

The words quivered with immediate regret, but Joe didn’t take them back. Caroline let the beat swell between them, then turned into the crowd.

Surrounded by strangers with sweaty flesh and dilated eyes, Caroline forced her way toward the stairs. Someone might have shouted, “Where are you going?” – but she didn’t turn, didn’t stop until she reached the second floor.

The bass was muffled and the watching faces had vanished. She relaxed and listened to the house – the settling foundation, wind in the eaves, and a softer sound, like fluttering eyelashes.Another staircase lifted behind her onto the third floor. She climbed it and found the night sky peering through the hole in the roof. The air was cold and fresh, and in the starlight she could see figures, heads upturned. There was a peace to their bearing, the hum of sleep and dreams.

She longed for bed, but a ride home would be expensive at this hour. Perhaps this room would do. She could stand with her eyes closed, mind unbound, thoughts drifting into the ether, far away from the party and her sorry life. She felt herself lift up, up, toward the open sky –

– and two pairs of sweaty hands closed around her eyes, yanking her down. Her feet tripped over the steps, sending her head-first toward the railing, which would have snapped her neck before she could scream.

But the hands caught her and set her upright. “It’s no fun up there,” two voices whispered. “All their thoughts have been eaten.”

Caroline regarded her saviors – twins in everything but height, one half the other’s size. They had round noses and marble eyes, bald heads tattooed with feral spirals. They wore red gossamer tutus and costume jewels with miniature top hats adhered to their skulls.

The tall one said, “Past your bedtime?”

“No,” Caroline snapped.

“This is a place for night people,” the short one said. “You won’t like it much here if you aren’t one of us. It’s best to leave before the party really starts.”

“Who says I’m not one of you?”

They cocked their heads. “You came here with others.”

“My brother’s friends.”

“You should find them and go. The Madame already warned you.”

Remembering the bouncer and her naked boldness, Caroline shrugged. “Why? They’re not my friends.”

“Then why are you here with them?”

“Convenience, I guess.”

They smiled, displaying little round teeth. “In that case, we know the best room in the whole house. Do you wish to see?”

Thinking of Jerry and his ungrateful sneer, Caroline said, “Hell yeah.”

The twins led her downstairs, passing a bottle of viscous gin between them. They moved in a fluid lilt with no resistance from the crowd, down beneath the chandelier and into a narrow hall. Caroline drank the gin and surrendered to the twins’ whimsy.

The hall ended in a staircase leading down into red darkness. Caroline hesitated – the air here was damp, sickly. “We’re going to see the Throat,” the twins said. “You don’t have to come if you’re afraid.”

“I’m not afraid,” she insisted; though no one had seen her come this way, and she had no idea where she was going. There were juniper berries in her eyes and she would follow the twins anywhere.

Descending into the basement, Caroline wondered if the gin had been spiked. They stood in a vast cavern, as if someone had hollowed out the entire neighborhood. The long dirt walls glowed red.

Something grabbed Caroline’s ankle. She looked down and caught a worm, oily and black, slithering into the dirt. Just the gin, she told herself, or whatever was in the gin. But she called out, “Are you sure this place is safe?”

“We come here every night,” the tall one said.

“It’s the safest we’ve ever been.”

“We found our way here by chance,” they said together. “We had many houses, many families. We frightened them all and they abandoned us.”

“This place is meant for those who’ve been abandoned.”

“Who make their home at the end of the world.”

They smiled.Caroline couldn’t help but trust them.

The twins brought her to a shoulder-width hole in the wall. A red bulb hung before it, dangling from a wire of black tar. The tall one pinched it between their fingers, put it in their mouth, and closed their lips around it. The membrane of their cheek ignited, an ombre of red and yellow. Between the layers of skin, Caroline saw their veins, intercrossed with fragile hieroglyphs.

They plucked the bulb from their mouth, erasing the veins. “Your turn,” they said, and handed it to her.

Her mind rejected the notion outright but her body did not listen. She took the bulb, stretched her jaw, and fit it inside. Tasting singed glass and heat, she almost retched – but then the feeling became gentle, spreading through her head, neck and core until every part of her hummed.

She took the bulb from her mouth and exhaled. A last electric caress went through her, healing a wound that she hadn’t known was there.

The twins gasped. “You feel it.”

She wasn’t sure what she felt. “I wish it could always be like this.”

In answer, the twins seized her arms and pulled her into the tunnel. The music was louder here, echoing like a giant’s heartbeat. “It’s singing to us,” said the twins.

“The Empty Hue.”

The tunnel squeezed so close they had to wriggle on their bellies. Caroline’s breath constricted at the thought of getting trapped in here.

The glow brightened, red reflected through the sweetest oil, trembling in time with the pulse. She lost sight of the twins in the thrum, melting and twisting her eyes.

“Here,” they said. “Look carefully. Don’t fall in, not yet.”

Through the vortexes of her sight, Caroline found herself at the end of the earth. She stretched her neck over the lip of a circular pit. It went into the soil, she thought – but the walls were not soil. They wriggled with a million tongues, lolling and wet. The red glow oozed from their pores, filling the tunnel and surging upward.

The bouncer’s warning shook Caroline back to awareness. She was not meant to be here, she was meant to be in bed, or at the hospital desk, helping someone survive. This was not supposed to be her nightmare.

As the red secretion overflowed, Caroline recoiled from the Throat. The twins’ faces were skulls in the light, skin flimsy as paper, mouths stretched in desperation. “Don’t be afraid,” they cried.

She thrust into the tunnel before they could grab her. The slighted hiss of the Mouth mingled with their cry. She scraped at the dirt and pulled herself through, into the catacomb. She found the stairs and leapt two at a time, as the twins howled at her back, “But you’re one of us! One of us!”

The crowd had thickened upstairs, nearly wall-to-wall. Caroline sliced a path through them with her elbow. She felt as if she’d already been swallowed and the house was just part of the stomach.

She almost didn’t recognize Jemima when her face loomed into view, pupils swelled beyond the iris, cheeks and eyelids bathed in red-black sludge. “Where are the others?” Caroline shrieked over the bass.

Jemima blinked once, twice.

“Where are the others?”

The girl flapped her jaw, revealing sludge in her teeth. “I don’t know who I am,” she said. “They gave me something. It came out of my eyes. I liked it at first, but now I don’t know who I am.”

Jemima drifted into another room, washed in soft, wet red. Caroline shoved her way after. Joe’s head bobbed near an unmanned DJ booth, confused but alert, alive.

Behind her Caroline saw a top hat and its twin, moving through the crowd with no resistance. Caroline tried to press away but a netting of flesh locked her into position. “The show is about to start,” someone said.

The music stopped. The crowd turned toward the DJ booth. The bouncer stood there, flanked by two naked, powerful women dyed hot scarlet, their limbs wriggled with hairlike growths, sleek wires of black and violet.

In front of them were three massive drums. They raised mallets over the skins and the crowd hushed. Smiling upon them, the bouncer swung her arm down and struck the drum. The room quavered with the impact, gutturally deep, felt rather than heard. The second woman followed, then the third. As the bouncer struck again, the rhythm became a tri-toned blast.

Through its reverberation, a pure, androgynous voice began to sing. It hovered alone, then other mouths fell open and joined, dissonant but clear. Their tongues rattled against their teeth, rolling the note into a force.

It was the ugliest and greatest sound that Caroline had ever heard. It amassed into a wind, shaking her to the point of rupture.

Joe did not hear. He stood too close to the drums, palms clamped over his ears, mouth ripped open in a yell. Next to him were Jerry and Jemima, no longer bored but terrified.

As the thrum deepened, Jerry’s eyes bulged outward, then popped in a spew of fluid and brain matter. Jemima’s head split down the middle; she palmed the sides and tried to push them back together.

The red glow of the Throat seeped from the basement onto the upper floors, setting the crowd adrift. The twins laughed against Caroline’s ear as she watched Joe’s skull explode. The spray lifted upward, quivered in midair, then broke over the revenants in a torrent.

Soaked in her brother’s blood, Caroline did not feel the floor evaporate. She did not join in the cry of triumph as the crowd heaved down, down, into a throat with no stomach, a mouth with no face. She did not share the ecstasy of non-being. There was only the twins’ voice, floating from the abyss:

“Welcome, sister, to the Mouth.”

There was no house, no crowd, only cold dark air. She huddled on the ground with her eyes closed, her joints too stiff to move.

Gray light began to seep through her eyelids. With a mild shock she realized it was morning. She and Joe were meant to have brunch with their parents in a few hours. Joe, whose blood was drying in her hair.

She opened her eyes to the daylight, squinting at its garish insistence. She sat on the peak of a barren hill, far from the abandoned cul-de-sac. The city was silent below; her ears ached at the emptiness. She thought of her bedroom, the hospital desk, everything she’d ever known, lost amongst those dull specks of color. It had been a different girl who occupied those spaces.

Caroline mourned her old self, but only for a moment. That life hadn’t been much – neither had Joe and his dreams, or his friends and their misbegotten fame. Only one thing mattered now. There was one place left to go.

The way to the house was clear in her mind. If the rideshare driver tried to find it again, he would come upon an empty field; but for her, it would show itself. She walked across the city and passed into the hills, following a beat that only she could hear.

Benjamin Larned (he/they) is a creator of dark queer fables. Their fiction is featured in Vastarien, hex literary, and Seize the Press, among others. “What Scares a Ghost?”, their story in Coffin Bell, was nominated for the Best Small Fictions 2023. Their short film “Payment” is streaming on ALTER. To learn more, visit curiousafflictions.com.