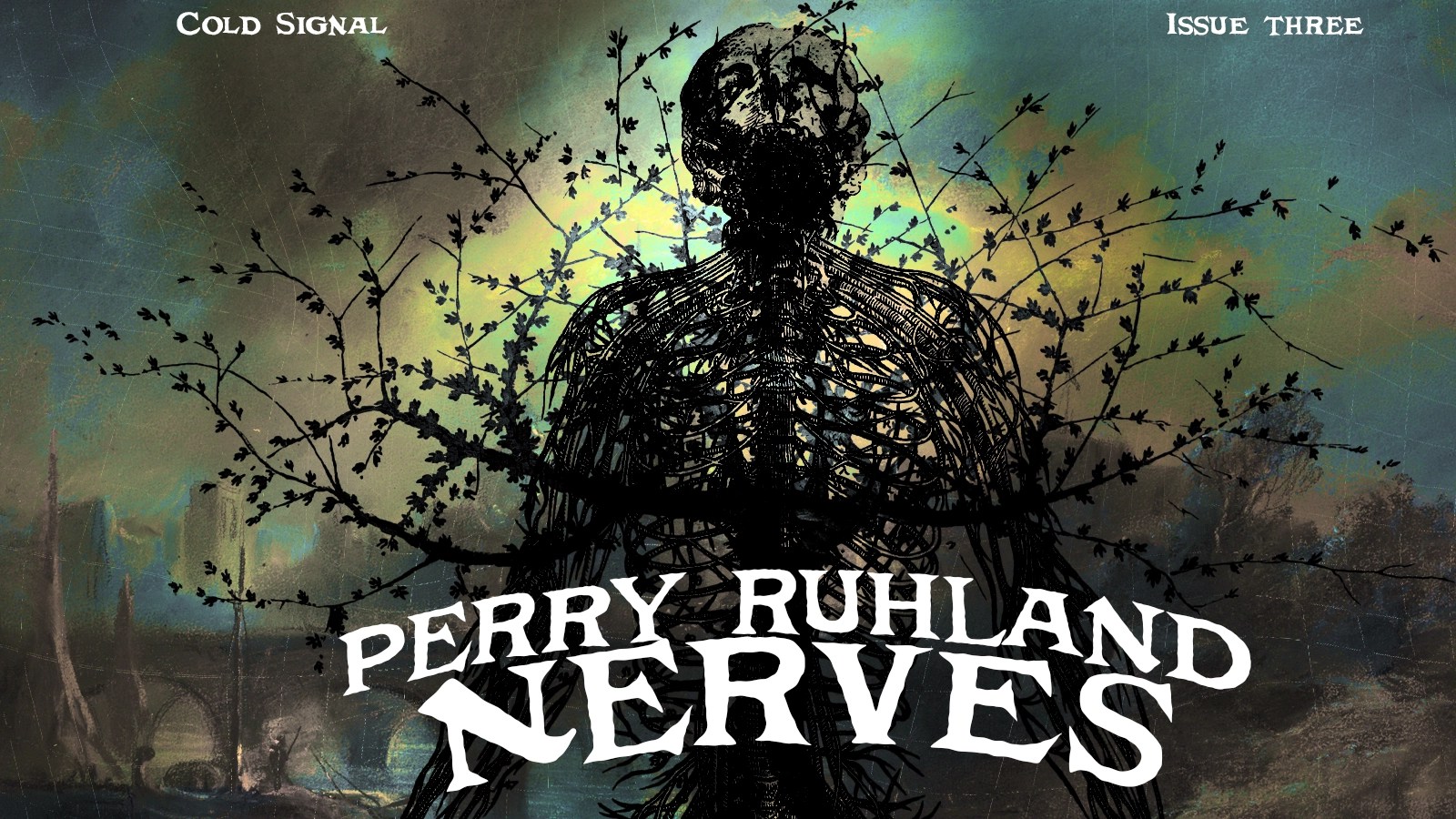

Nerves

by Perry Ruhland

Nothing would cohere, everything collapsed. The stories were half-formed things, shoddy skeletons wrapped in fat. They were written, abandoned, the drafts thrown out. Sleep was lost over these discardings. Failure hung heavy; not work, friends, love nor porn could shake it. Rest, like reading, became impossible. Only meditation provided an escape, and only after great effort. First, the awareness of nostrils and lungs, the organs and their connective path floating suspended in a void. Gradually they were joined by the skull, stooped shoulders, convex spine, spread hips, folded legs — each addition reified, all things with density now, volume. Itches and aches were things, even attention was a thing with an amoebic crawl across the hollow head. Thought was sublimated into posture, the conduit for sensation.

The body observed the distance between the head and the television whispering in the apartment above. There was the electric buzz in the walls, the air conditioner in the adjacent room, and depending on the night, the dishwasher rattling in the room adjacent still. Outside roared the dip and rise of planes coming and going from the eastern airport. Inside, the tinnitus, the ache in the back, the weight in the neck, the pinch across the brow sharpening.

Some meditations were followed by writing. The practice was slow, painful, and generally unproductive. A narrative formed nonetheless. The story follows a man, nameless, attaching a metal box to a vent. This vent is in the posterior of an old house with darkened windows. The man is crouched in the garden. He wears a trenchcoat, a fedora, and sunglasses through the night. He’s installed the box to the vent. His hand in blue gloves flicks a switch on the box. It rumbles, he waits beside it.

When a cloud covers and uncovers the moon, the man reaches into his coat pocket and withdraws a sleek respirator. He picks the lock of the back door, moving slowly across kitchen tile, a hardwood floor. There are voices in the living room. Wisps of green gas hover about the ceiling where the fan carries dust. Two bodies lay unmoving on a couch, arms of one wrapped around another, a head nestled against a chest. Eyes are closed, dimples suggest pleasant dreams. The light of a television bathes the figures; faces onscreen shriek as they’re briefly eclipsed by the man.

Up the creaking stairs, down a hall, past rooms with occupants frozen as they were, green gas coiling about their heads. In one room, a man and woman beneath a blanket do not stir when their door is opened or shut. The man treads across the floor, stands beside the bed. The sleeping couple are smiling as the blanket is peeled from their bodies. The man in his underwear spoons the woman, moonlight on the curve of his back.

The man in the respirator pulls the man from the bed. He slams on the floor and neither sleeper stirs. He’s face-down on the wood, legs splayed, arms slack besides him. A powder-blue finger traces the ridge of spine down his neck and to his hips, dipping just beneath the band of his briefs. The man is on his knees, mounting the sleeping man’s back. Blades flash when he reaches again into his coat and withdraws a pair of wicked shears. The steel tips sink into the sleeper’s flesh around the lumbar. The sleeper’s body twitches as they sink in, but he does not stir.

Over the course of some pages, the man carries out the task. He disposes of his noxious device, shears, gloves, hat, glasses, coat, boots, and respirator in a dumpster. The vertebra he buries under soil in a concrete garden. In plots to the left and right, spinal buds pierce the surface. More developed trunks bend upwards and grow mandibles or mastoids. Few have matured into skulls — soft skulls, lumpy skulls, skulls cratered or gaping frozen screams — misshapen flowers opened to the sky. Nervous roots tangle in the dirt.

Here it grows vague. The man might see himself in a conspiracy with nerves. Feeling great sympathy for the spine, “a frowning thing”, he attempts to liberate them from their human hosts. Alternatively he might divine futures in the development of their mimetic vertebrae, gates to sacred realities forged in fresh-grown backs. He could link the misshapen skulls with computers, wire them down the spinal cords, and hear the binary howl of the nervous garden. None of this would happen, for there in the garden, the world calcified. Nothing would develop, nothing could stick, and no matter how far back the thread was chased there was no alteration to this fatal episode. The story slipped into a deep, narrow hole beyond retrieval. Failure remained.

So it came time to run instead, eat or starve on whims while each night growing intimate with aches. The more closely one inhabits a body, the more that body grows strange. Alienation, not from the recognition of one’s own dimensions nor the gradual unveiling of how many once-invisible processes churn “behind the scenes”, but from the simple awareness that bodies are matter. Meditation made this undeniable. The hard solidity of the floor reached through fabric, skin, fat, and muscle to find itself reflected in bone. The aches and tremors of the lower back were cracks and scratches dispersed across the whole of the apartment’s flooring. The air conditioner hummed tinnitus. Every itch on the scalp, knee, or crotch stained the walls. Planes roaring in the distance stretched and snapped these illusions; no longer the body with its newly annexed exteriors, but rattling, soaring, purely headless. The experience passed with pain, bones screaming in return, the afterimages of a horizontal abyss deep whorling blue behind shut eyes. Mist lingered as another dimension draped across the world of aches and cracks and reasserted themselves with each passing plane. Slight variations in shade opened vistas of sensation. Within vertiginous blues, opaque leviathans collided and dissolved, tearing seamlessly ahead. A landscape seen not as the eye or imagination sees. Feeling cold without feeling cold; having felt nothing at all.

Then seeing as the eye sees through a tinted window, dark clouds rushing by. The inside of a cockpit: narrow and curved, lights blinking from an array of dashboards and switches across the walls and ceiling. Two waxy pilots sat at the controls completely silent, and so was the plane.

Outside, a cabin with a dozen rows of chairs situated on either end of a thin walkway. Lights dim on vague figures in wide-brimmed hats. There weren’t any vacant seats but the bathroom door was open. I was already there stooped on the toilet, naked but for paper slippers. My back — only seen in pictures and reflections — curved in on itself. The dip in my lumbar, so familiar to the touch, was at once deeper and less impressive than I’d imagined.

Under skin and red muscle, a metal scaffold wrapped the spine. Twin cobalt chrome rods ran parallel down the bones connected to the back via pairs of bulbous screws on each vertebrae. The pedicle screws were inserted bilaterally with a hand drill following the midline incision and steel tools holding wet flesh away. Flecks of bone graft sprinkled the viscera while excess flesh collected in a stainless steel dish.

Elsewhere in rooms vaulted like cathedrals bodies lay on metal slabs, angel wings of skin splayed from their backs. Low white moons exposed stenosis, kyphosis, arthritis, scoliosis, spondylosis, fractured bones and herniated disks. A murder of gloves picked away with scissors, gouges, and retractors. Within the naked spines the dreams of the anesthetized festered, the anxious muck of self bleeding down a ladder of ancestral traumas. Holograms of schools, jails, silent planes, city blocks, black mansions, concrete gardens and flooded basements sprouted in the vertebrae. In one column, a hunchbacked woman walked the limestone arcades under the pursuing echo of her great-great grandmother; in another, a bejeweled amusement park grew across a Jurassic forest, baroque stitchings of rail weaving through thick-stiped ferns.

The park was dislodged with the excision of a brown and punctured vertebra, the bone discarded in a stainless steel dish. With gray organs and excess flesh it quivered in the incinerator’s flame. The pain merged with tumors and lungs in an undifferentiated goo. The goo burned down to ash. In black smoke nightmare climbed the chimney to pollinate the sky.

After Thomas Moynihan

Perry Ruhland is a writer based in Chicago. His writing has previously been published in Baffling Magazine, The Book of Queer Saints, Chthonic Matter Quarterly, Vastarien Magazine, Weird Horror Magazine, and ergot.press. Learn more at perryruhland.com.