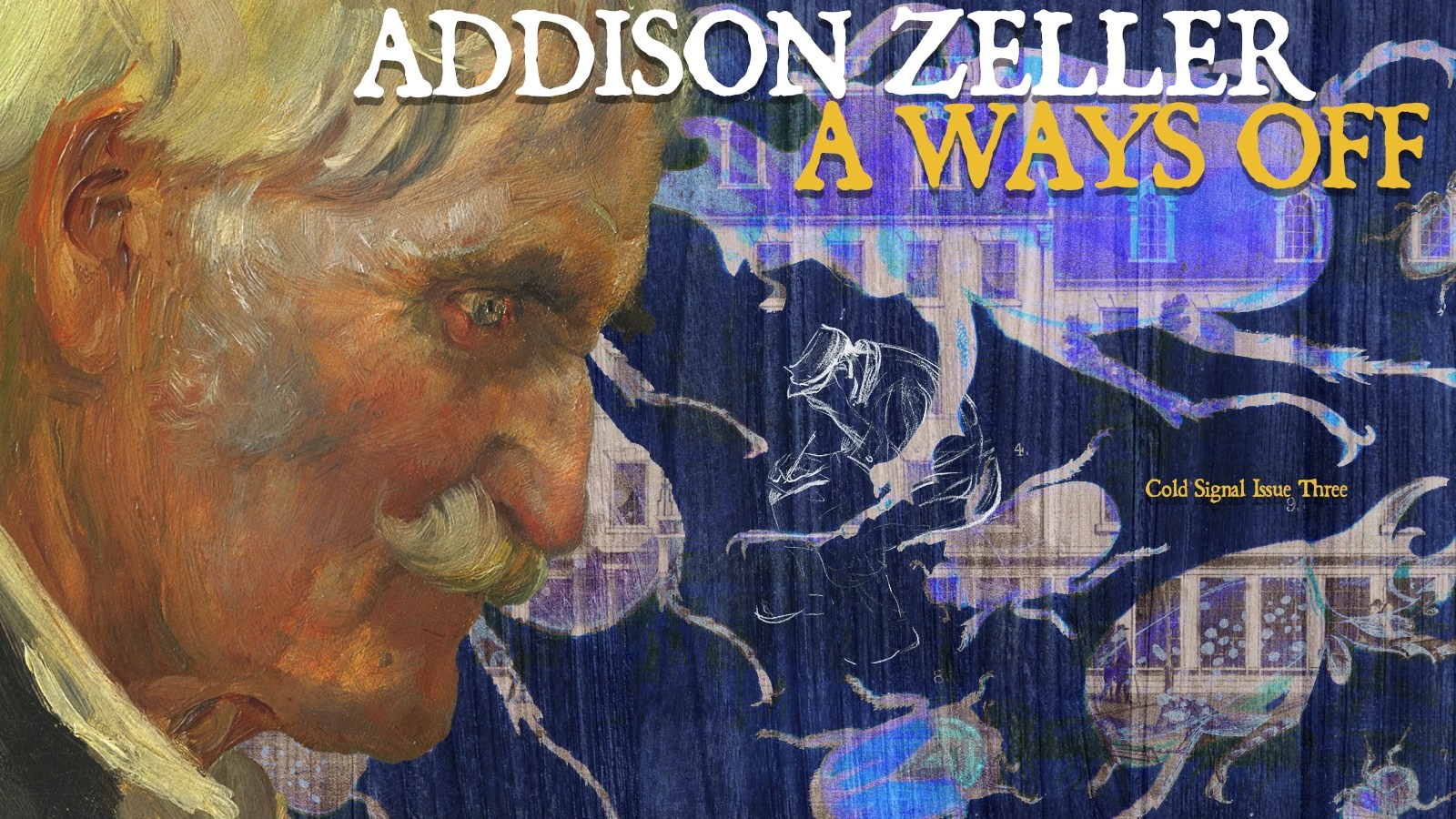

A Ways Off

by Addison Zeller

The hotel restaurant was closed. Beetles had eaten the carpets. “We used to sell oysters,” the manager told me when I handed in my references. “These don’t matter,” she said, waving a pen as if to make them disappear, “but what did you do during the gap?” “Prison,” I said. She asked what it was like. “There are worse things. We stood in the yard, wherever the sun was pointing, and followed it when it moved.” “Like pigeons,” she said. She explained she could hire me because—if the owner was right—the hotel would shutter in six months. She was taking pity on me, I’d won her over. She had a framed poster of Townes Van Zandt in her office. He had a cigarette in his mouth and a Stetson pushed back over his wool collar. “You know who that is?” she’d asked. “Sure,” I said, “it’s the same photo of him you always see.” She handed me a green apron and told me to shadow Lynn at the night desk, 9 to 3. “Graveyard shift,” I said. She laughed: “They all are.”

A man called a few times in the night to adjust his ETA. The highway was stormy. “Might as well relax,” Lynn told me. If I wanted to go up to any room, turn on HBO, take a nap, I was welcome to. I sat in a peeling red leather chair in the lobby and watched the awnings flap in the rain.

A brass button popped off the chair. I couldn’t screw it back in, so I closed my hand and looked up to see if Lynn had noticed. Off the desk, past the glass doors, a man stood in the bar with a towel over his shoulder. A phone lit his face. I buried the button in the cushions, then the phone went dark and his face disappeared.

I dozed in the chair, waking only when the phone rang with an update from the man on the highway. At 3, I biked to the shelter. It was still raining.

Lynn was a nice girl. She’d been in the job three years. She was divorced, one kid. Her hair was fiberglass pink. She made dollhouse furniture. I found her page on etsy and thought of buying a lamp, but the price was too steep; besides, in the shelter, where would I put it? The late shift was good, she said. Gave her time to spiritually regenerate. Especially on rainy nights. They had energy. The problem was leaving the kiddo. She couldn’t keep having her mom over if she wanted to self-actualize.

A few weeks before the hotel closed, she asked me out for a drink. I slid into the booth and she pulled out her phone to set up a night when we’d have another drink. That went on a while, sporadically; she mistook me for an answer of some kind.

I don’t know who found the hotel periscope, or who knew about it other than Lynn, but she showed me when it was raining—maybe on the night I started. It wasn’t a real periscope, just a crack in the wall on the second-floor landing: a vertical slit where soap-green wallpaper met dark wood paneling. “You got to squint,” she said, but I couldn’t do it right. “Can’t you see the house?” “No,” I told her, “I don’t see shit. But I don’t see shit normally, it’s nothing new; I got paint in them once, working rollers. Maybe I see wet bricks.” “That’s the Fargo House,” she told me, “where the Fargos lived? They built this place: it’s in the walls.” It took till daylight, but I made it out. A wall of bricks, slick with rain, a window ledge, even a window; I guess they built the hotel around it, which is why occasionally, pushing the laundry bin, I’d pass oak leaves carved in the paneling, and stained-glass windows, and gas lamps.

“It was the original property,” Lynn said. “It got built over when they sold the lot.” Screwing my eye around, I made out the bedroom: a potted plant, a canopy over an iron bed, a few shapes under the blankets.

“Wish I was in there,” I said. “Hell, that’s how I want to live, naked on a huge bed, getting old.” “Keep dreaming,” she said. A lamp switched off and the afterimage floated in my skull like a brainstem. “You better go down and de-pulp the juicer.”

The orange juicer in the breakfast nook had choked on pulp; I took a spoon and scraped it out, then snapped the plexiglass panel back on and watched the oranges begin to unravel from their peels as they squeezed out juice between the cogs. After that, I took the cart up the service elevator with refreshments of shampoo and body wash for the guy in the occupied room. He’d been there a year or more; I think he was a mayor once. I knocked on his door until he told me to come in. “Got you some soap and body wash,” I said, “and some of that fresh OJ.” “Good, put it down,” he told me.

He held up something glinty. “Recognize this?” He was an old man; he had those veins in his head, the thick ones that look like they belong in the jungle. It was impossible to see his eyes, they were under too many eyebrows. “That’s a button,” I said, peering at the object. “That’s right,” he said. “Know where it comes from?”

“No, sir,” I answered, but I was lying: I knew right away. “That’s what I thought,” he said, “that’s OK, son; looks like we got a little secret.” He flicked on a lamp over his seat so I could see the button even brighter: the button from the leather chair. I trembled as I put out the body wash and shampoo. “A little secret between you and me,” he said. “That’s right, sir,” I said, “and let me know if you need any more OJ.” He smiled at me, a good long smile, and slid the button into a crack in the wall. I didn’t even hear a clink. “So we understand each other,” he said.

“Can I do anything for you?” I asked, and he shook his head to say “Not yet.” The hotel was going under soon, he reminded me, the lot would get sold; inevitably, the building itself would be demolished, everything’d go, there’d be a general liquidation: the passageways, the periscope, the carpet runner and rods, even the button would be scooped out of the wall—he paused to caress the wallpaper the way an owner caresses a horse—but work still needed doing, staff had to be retained; would I like to be retained? “Yes,” I said. He rose and slapped my cheek gently, then held the door and wordlessly permitted me to leave.

Our condition changed rapidly. The hotel was sold and torn down. Soon the only part left was the house, stripped clean like a beached whale, a notice on the door. I answered. I was required by law to prove I was working or seeking work, they needed someone, and the house didn’t look so bad now that it was out of its shell; there was patriotic bunting on the porch railing and indoors, over the mirrors and the sides of the walnut staircase and atop the wardrobes; silk-spinning beetles were responsible for the other decorations, which hung from the ceiling like huge snowflakes; a pheasant with an indigo breast glowed cheerfully under a glass bell on a console in the sitting room. “Does the family live upstairs?” I asked the man who interviewed me, a servant who looked like a dyed egg, but he told me it didn’t matter for my purposes, I wouldn’t interact with them directly.

As for my duties, they were light at first, but would increase with trust, as would my pay. “Then I’m approved?” I asked. He explained that he already considered me retained: in essence I was fulfilling an obligation, a debt, and didn’t I need the work? “Yes, I do,” I assured him, “I really need it, but I can’t promise I’ll know what to do right away.” He smiled kindly and shook his head. “Our only stipulation,” he said, “is a clean record, which you will work up to, and your patience, because, as you can see, we are experiencing a time of transition.” He waved his hand emptily around the sitting room, which had nothing but decorations; a low opera sound floated up from a radio I couldn’t see from where I sat. He let me go get my things, which I brought from the shelter in my backpack. I was entitled to a bed on the top floor, in what had been the servants’ quarters back in the day; it’s where I’m writing now, in the dark, under a low whitewashed ceiling. A TV is on, but it receives nothing: only a gray light that shakes now and then to release a face or an elbow, a line of dialogue or musical sting from whatever program the static hides.

My only night duty was to listen for visitors. A bell would ring over my bed to let me know. Then I could go down and admit them. “Can I shower first?” The servant permitted it, so I took a shower once I’d put my things in my room. There was no one in the corridor, which had a fuzzy, tenuous quality, the way things do at night if you keep your eyes open long enough. A soft alive atomic dust crackled in it. I could have gone downstairs and no one would have noticed, but I didn’t. I took my shower and returned to my room, a towel over my shoulder, and sat on my bed as I waited for the bell to ring. (It’s a little bed, practically a cot, with a brown papery sheet that leaves small coils of lint on my clothes, fingers, and the mattress.) I wrote for some time. The bell never rang. I was writing a letter to the woman I loved. That was how far back I’d gone in time. I was writing a letter before I had met her, before we existed. The hand wasn’t even mine; the letters were remote and vague. I told her what I could: that I wouldn’t see her again, that the paper would be cold by the time she read it. When I was done, I picked up the sheets—my fingers didn’t feel them, I’d grown so transparent—and folded them into an envelope, but I no longer had the power to seal it with my tongue. (In time, someone will read and deliver it correctly.) My phone still worked, so I scrolled Twitter while I could. It was no longer possible to like tweets, but I read enough to feel present in the world, like a floater in its eye. “Lights out at 12,” said the servant, knocking on my door. The phone went dark at midnight, my face disappeared.

Addison Zeller lives in Wooster, Ohio, and edits fiction for The Dodge. His work appears in 3:AM, Epiphany, The Cincinnati Review, minor literature[s], and many other publications.